Far from view, buried underneath countless headlines, and lost from U.S. history books is a tragedy few Americans know about. Why this particular catastrophe remains relatively unknown rests on facts and opinions as numerous as the canyons of Western New Mexico.

Author’s note: Reporting for this story took place in the winter of 2014.

Outside Gallup, New Mexico, near the end of Highway 566 on the Navajo Nation, is an enclave of houses snaking through dusty hills. The community, Red Water Pond, lies between the old Church Rock and Quivira uranium mines. The once booming uranium mining operation has left few remains. Houses stand in small clusters, often with miles separating neighbors. Barbed wire cuts across the vast landscape dividing parcels of land. In the past, a steady stream of trucks would run up and down the highway, transporting raw uranium for processing. But once the mines closed in the early eighties, little to no significant cleanup occurred. The pursuit of uranium left massive amounts of contaminated material in its wake, scattered across the reservation.

The trouble with uranium contamination, unlike an oil spill, is that it is tasteless, odorless and invisible. But it’s there, stalking the landscape. It floats invisibly in the air, covering livestock, sinking into wells, and seeping into fields.

The Navajo are no strangers to the pursuit of uranium, nor are they strangers to the lingering impacts years after the mines were abandoned. Uranium mining on the Navajo Nation took place during the Cold War for atomic weapons and ran into the 1970s and early 1980s for energy consumption. On July 16th, 1979, a dam break at the Northeast Church Rock mine released 94 million gallons of radioactive mine tailings and 1,100 tons of solid radioactive mill waste into the Puerco wash. The contaminated materials and water were then swept into the Puerco River, and eventually, out to the Little and Big Colorado rivers making the spill the largest of its kind in U.S. history.

Few Americans know about the accident because of where it took place: far from any major U.S. city; who was affected: a small and marginalized population of people; and how it was handled: contrary to the Navajo Nation’s government request, New Mexico’s governor refused to deem the site a federal disaster area, thereby limiting federal aid.

The disaster in 1979 more than likely aided in the closing of the mines on and near the reservation. Coupled with market prices leveling out and less demand, operations slowly wound down. Today, the U.S. EPA estimates that there are a total of 500 abandoned uranium mines scattered across the vast Navajo Nation, a landmass about the size of West Virginia. Each would require millions of dollars to clean up. Since 2007, there have been three separate environmental remediations of Red Water Pond. Remediation, a sterile word, is used to describe the removal of residents from their homes, having to instead live out of hotel rooms in nearby Gallup.

With another move looming, conversations at community meetings are a buzz of uncertainty. Where will they live during the cleanup? How many houses will they be given if they decide to move back? Will it be truly safe to return to their homes?

The eastern side of the reservation, where the Church Rock dam break took place, is known as checkerboard land—a crosshatching of mixed-use ownership. Issues surrounding access to mining and grazing have long been a point of contention for both internal and external interests. Today, what is left of the Church Rock mine, owned and operated by the company United Nuclear Corporation (UNC) at the time, can be found some seventeen miles outside of Gallup, New Mexico. Set on private land, the mine was straddled on either side by Navajo Nation Tribal Land.

Up near the former UNC cell ponds, which were part of the refining process plant, all that remains from the 1979 dam break are piles of gravel, flat planes filled with brush, and some access roads. Today, the only signs (few and far between) on the fence marking the site warn of private property. It is unclear to the passerby that there might be any possible dangers to those who live near this site, and many like it, across the reservation.

Despite a long period of inactivity at the sites, the remediation of these mines has been slow. Those that live near former mine sites are continually exposed to contaminated material. Even people far removed from a mine can be affected as loose contaminated dirt is carried on strong winds covering trees, livestock and homes alike.

Adding to this is the contamination and desecration of religious sites. Some argue that former mining sites hold cultural and historical artifacts. Set on private land, these locations are difficult to access barring any sort of cataloging and protection. Others living downwind from abandoned mines or monitored collection sites find areas sacred for prayers to be covered in irradiated dirt. The remediation process, then, is not only one of logistics but of tangible long-term health and cultural impact.

There are roughly 871,000 cubic yards of contaminated mine waste that still need to be addressed in the Northeast Church Rock area. If left up to residents in Red Water Pond, irradiated material would be transported to a facility in Utah. The cost for that would run approximately $293 million. The alternative, and most likely solution, would be to transport the mine waste down the road to the current Northeast Church Rock facility—a decision based on economics. There are, however, serious concerns over the conditions of the local waste site. There is little control over contaminated water and air particles, and there are no warning signs alerting residents or passersby of the possible dangers of the location. When reached by email to discuss these matters, United Nuclear Corporation Vice President Larry Bush declined to comment.

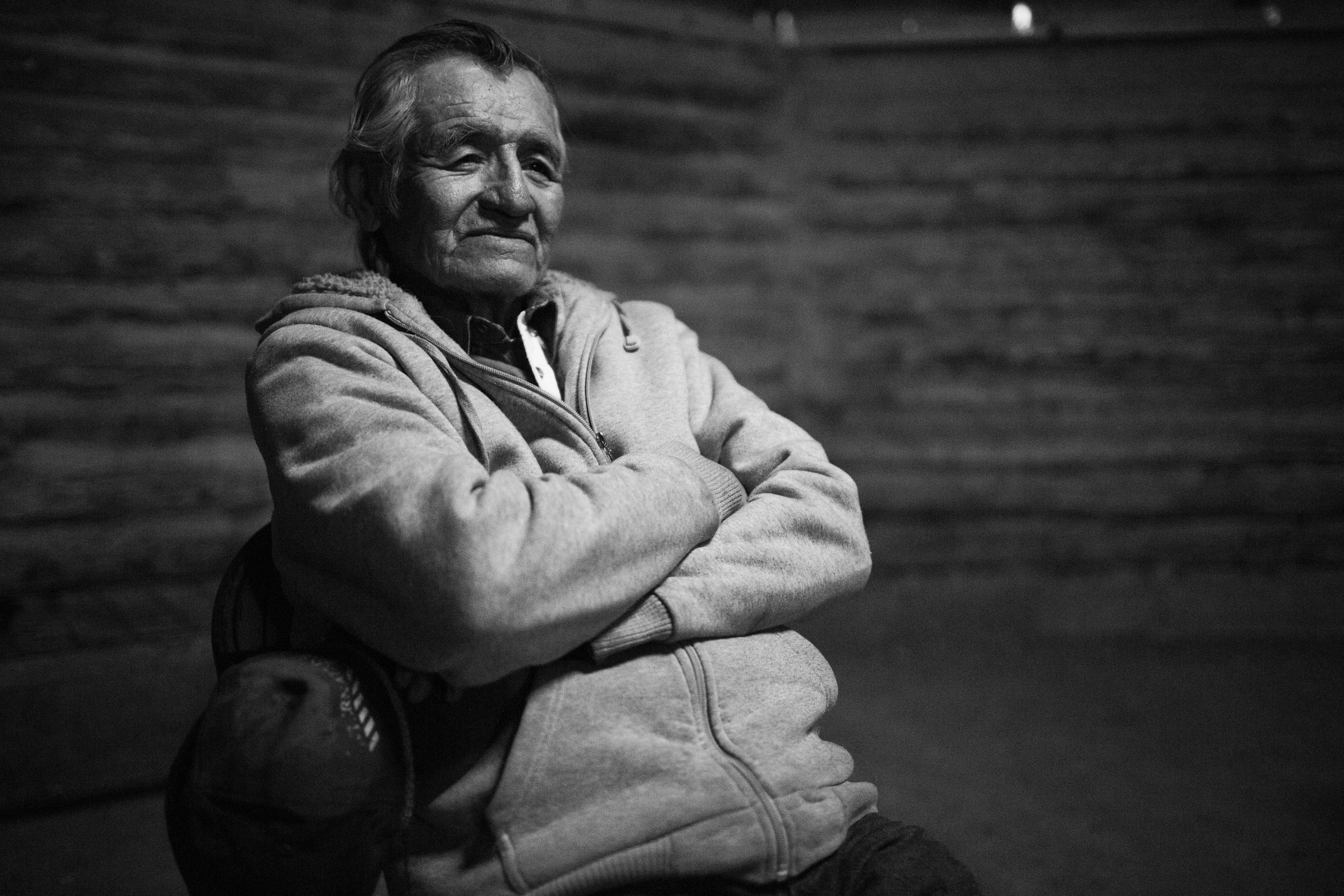

“I have a beautiful well that’s been used since before the white man came. Nowadays I can’t use it because of the Gulf Mine, four miles east of here,” says Bronco Martinez as he sits in a traditional Navajo hogan just down the road from the site of the former mine. Owned and operated by Chevron, the mine operated for only a few years at the end of the 1970s. Despite a short life, its legacy continues on today. “It contaminated that well. I cannot drink it, wash with it, or wash dishes with it. It’s full now, but I can’t use it. I’m blocked from that well,” he says. Almost 30 percent of Navajo people living on the reservation lack direct access to water. Martinez now hauls water from Gallup, over an hour away, on a regular basis not only for himself but for his six appaloosa horses.

There is a bitter irony behind Martinez’s words.

“My grandfather was Patty Martinez. They say he was a Navajo legend that is supposed to have discovered uranium by Mount Taylor called Haystack Mountain,” he says. Living roughly twenty miles east of Red Water Pond, Martinez, who grew up not far from Albuquerque, has a direct line to the origins of uranium mining on the Navajo Nation. The uranium mining that took place in and around Haystack Mountain was one of the largest open-pit mines of its kind. In its heyday, the mine produced 300 tons of ore a day. Now, the once-massive pit is covered up with dirt and weeds.

The impetus for cleaning up the uranium mines on the Navajo Nation began in earnest with the October 2007 hearing on the Health and Environmental Impacts of Uranium Contamination in the Navajo Nation. It was during this hearing that Chairman Henry Waxman said, “For decades the Navajo Nation [lived] with the deadly consequences of radioactive pollution from uranium mining and milling. The primary responsibility for this tragedy rests with the Federal Government, which holds the Navajo lands in trust for the tribes.”

Personal testimony and scientific evidence from the hearing point directly to the negative health impacts uranium mining and related toxic minerals exposed during mining operations have had on and near reservation land.

Between 2004 and 2010, the Diné Network for Environmental Health Project worked with nearly 1,000 Navajo participants to determine the impact of non-occupational uranium exposure. The independent study gathered information from self-reporting participants. “People living in areas with [the] greatest number of mine features can have twice the risk of hypertension when all other significant factors—kidney disease, diabetes, family history of disease, BMI, age and gender—are accounted for as the baseline,” the report found. The report was reviewed and approved by several bodies including the National Institute of Environmental Health and Science. The Navajo Birth Cohort Study is extending this research by looking into whether exposure to uranium waste affects birth outcomes and childhood development on the Navajo Nation.

From 2008-2012, the U.S. EPA—in coordination with the Navajo Nation EPA and other government agencies—began assessing the scale and impact of uranium mining on the people of the Navajo Nation. Investigation and litigation of responsible parties ensued. The 500-plus abandoned mine sites were located and marked for remediation. Known as the Five-Year Plan, eight locations were given high priority. Of those, just one, the Skyline Mine in the North Central part of the reservation, has been cleaned up. The budget for that cleanup was $8 million dollars. The other seven, like Church Rock, are still undergoing different stages of research and remediation. As of 2014, a new Five-Year plan has been created to continue research and cleanup of key locations.

At Haystack One, an hour-and-a-half drive east of Gallup, faded signs warn that the land beyond the fence is contaminated with uranium. Randy Nattis, a Federal On-Scene Coordinator for U.S. EPA, stands just outside the fence line. Set back from the former open-pit mine, now covered in brush, are several trailer homes. “To the naked eye, you’d think that this is just a healthy pasture. If I had my ludlum meter, otherwise known as a Geiger counter, we would be in an elevated area right now,” says Nattis. “If it’s over a certain threshold, sometimes twice background or three times, then you’re at an investigation level. Here we are probably twice background. Inside the fence line and we would be fifty times background in no time.” As he speaks, large gusts of wind swirl contaminated soil around him.

Determining who is responsible for the cleanup of a site involves research to track down the companies who once mined in the area—assuming they still exist. If they do, then either by choice or by court order the companies start to figure out a plan to clean up. If the U.S. EPA can’t determine a responsible party, they are stuck handling the clean up themselves. Nattis is hopeful that clean up of the Haystack mine site could be addressed soon, based on time-critical conditions of six months or less. But not all abandoned mine sites are flagged as such. The conditions for immediate action are based on direct threat level to residents and other determinants. Speaking about the site at Haystack and the importance of having responsible parties involved in the remediation, Nattis continues: “A mine like this, if we had to remove all the contamination from this property, and move it somewhere else to an offsite repository or disposal off the reservation, could cost up to $20 or $30 million dollars. We’re talking about $60 or $80 million dollars to do the other two or three other sites [here] if we just acted on our own.”

The relationship between the United States and the indigenous people is complex. Native peoples across the U.S. have often, arguably, been sidelined and ignored. The legacy of war, forced migration, land grabbing and cultural eradication taken out on native peoples by the U.S. Government is well documented. It should be no surprise then that issues such as dealing with uranium mining contamination on and around Navajo Nation are slow to be addressed—if addressed at all. Coordination between the U.S. and Navajo EPA takes copious amounts of time, planning and money. Everyone involved agrees the legacy of uranium mining needs to be addressed. However, arguments over what clean-up looks like all depend on who you talk to; residents, tribal leaders, corporations and U.S. government officials all have different ideas, wants, and needs.

It will be multiple generations before the initial contaminated sites are fully dealt with—let alone any new contamination that may now occur if new uranium mining is allowed to occur near Navajo land. Meanwhile, in between the litigation, scientific research, headlines, and government reports are people living with the lasting effects of an industry they cannot ignore.